Last February, in honor of Black History Month, I watched two different documentaries about Miami’s Black history (and present): “Swing State Florida” and “When Liberty Burns.” Both films made mention of something I had never heard of: a physical wall that separated — and segregated — the Liberty Square housing project in Liberty City from the rest of the neighborhood.

As a Miami native who likes to think of herself as being a little bit better versed in local history than the average resident, it was both shocking and humbling that there was something as monumental and significant as a physical wall segregating any part of Miami. I needed to know more, and I needed more Miamians to know, too.

My first phone call, months later, was to Dr. Marvin Dunn, a local expert on Black history and professor emeritus at FIU. “It shocked me to discover that this race wall had ever existed,” I said to him, using one of the many terms that now identifies the wall. Nearly before I could finish my thought, he replied, “Which one?”

The Liberty Square Wall

Remnants of the Liberty Square wall today (Grace DeWitt/The New Tropic)

The first government-subsidized public housing complex in the American South, Liberty Square opened Feb. 6, 1937 to relieve the overcrowding of what was then known as Colored Town, today Overtown. Designated as the area for African-Americans to settle when the City of Miami was incorporated, living conditions in Colored Town deteriorated as a growing population remained confined to the area under Jim Crow laws.

The city would soon pursue an expansion of Liberty Square, “prompting bitter objections from [Liberty City’s] White residents, who had been promised a 20-acre buffer strip between their neighborhood and the housing project,” writes artist and professor Chat Travieso, one of the few scholars researching the nationwide use of these race barriers.

“As a condition of the Liberty Square housing project [expansion] being built,” said Dunn, “the Whites insisted on a wall. Not only did they want the wall, they wanted and got huge trees, Banyan trees, built along the wall.”

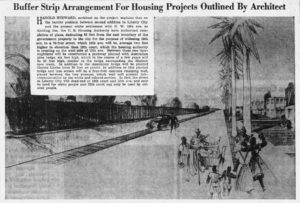

Clipping from The Miami Daily News, showing an architectural rendering of the Liberty Square wall, July 16, 1939. (Chat Travieso / Places Journal)

“Some of those trees still remain,” he added, giving meaning to the trees I’d see when I drove up to Liberty City to see the wall for myself. “The intent was not even to have visual access into the White community by having the wall, as well as these trees built along it.”

The Coconut Grove Wall

Top: A portion of the Coconut Grove wall to the rear of the Mariah Brown house near Main Highway, Bottom: the wall seen near the corner of Jefferson Street and Charles Terrace (Grace DeWitt / The New Tropic)

“There was also a wall built in Coconut Grove that reached from Main Highway all the way through the Grove to LeJeune Road,” continued Dunn. “That wall was built in the 1940’s to separate the White and Black sections of Coconut Grove.”

As 25-year-old reporting — assembled by a patchwork of what little information about “the wall” exists in anecdotes and archives — seems to suggest, the wall similarly came together in patchwork fashion as a series of walls, gaps, and barriers. There’s the wall behind the Mariah Brown home that Dunn directed me to, an unfinished block of Marler Avenue and broken stretches of Hibiscus and Plaza Streets, and a somewhat better-historied stretch of concrete in an area once known as the St. Albans tract.

Peering east through a fence on Douglas Road between Franklin Avenue and Loquat Avenue, down what would have been the second block of Marler Avenue (Grace DeWitt / The New Tropic)

As Travieso writes, this section of the Grove wall’s construction was “the result of a quid pro quo with the FHA,” the Federal Housing Administration. He describes the nationwide practice as redlining cast in concrete.

“The Coconut Grove wall, like so many others, was built in the postwar decade to appease White residents, in this case a group protesting construction of affordable all-Black duplexes in what was then known as the St. Albans tract,” Travieso explains. “After a multiyear rezoning battle between builders and White homeowners, the latter compromised. ‘Under a tentative agreement, the St. Albans tract owners would grant a 30-foot buffer strip, a six-foot wall topped with wire; then a 50-foot street with a row of single family houses on the farther side of the street.’ In exchange, White residents would drop objections, clearing the way for developers to access FHA mortgages.”

“Now, Blacks were not allowed to buy property on the other side of the wall, the White section,” said Dunn of the Grove wall. “White people could — and did — buy land on the Black side of the wall.” Though his words refer to the past, they’re reflected in the present as tracts of land in what is formally known now as Little Bahamas of Coconut Grove (colloquially, Black Grove, or somewhat more controversially, West Grove) increasingly hit the market for $700,000 to $800,000.

“This is your opportunity to build your new Dream Home!” reads one property listing, down the street from the Mariah Brown home. “Rarely available 5,000 sq.ft. vacant lot in the heart of Coconut Grove. This lot is down the street from Main Hwy & Douglas Rd. in an area that includes million dollar homes,” the listing somewhat vaguely states. Attached are photos of a grassy lot, with two shotgun-style homes and a wood-frame building, all typical architecture of the Bahamians who settled the Grove, in view next door. “There used to be a house on this lot, [sic] that was demolished. This is an opportunity you won’t want to miss!!!”

The South Miami Wall

Top: The South Miami wall extends west from SW 64 Street… Bottom: And north from SW 62 Avenue (Grace DeWitt / The New Tropic)

“There was also a wall built in South Miami,” added Dunn, as our conversation continued. “That wall was also built for the same purpose, probably as early as the ’40s or ’50s, again to separate those communities. As a matter of fact,” he remarked, “that particular wall was rebuilt more than once” — always with segregation in mind.

My next call was to Dr. Anna Price, the first Black mayor of South Miami, who held the office in the ‘90s after moving to South Miami in 1983. She says that the wall stands at its original height, but further details of its origins are murky.

“We are believing it was [built] in the ’50s,” she says, echoing Dunn’s estimate. “South Miami had an ordinance… and the ordinance says, ‘An ordinance providing for the segregation of the White and Colored citizens of the City of South Miami, Florida,” she shares. “Now this ordinance was signed on the 17th of January in 1928, so we had an actual ordinance that prohibited Black people from purchasing property on that side of the wall.”

“There was a sense among some White people that a physical barrier would stop Blacks from wandering into the White area, and would restrict the presence of Blacks in sections that were designated for Whites,” explained Dunn. “It was also a way for the police to be able to contain Black people and [for Black people to] know the boundaries that they were supposed to respect. And, therefore, they’d be arrested if they disrespected those boundaries. So these walls had psychological and physical components to them that had the basic impact of having Blacks know their place: it is on the other side of that wall.”

A near-missing chapter of Miami’s collective history

If by this point in the story you’re feeling similarly stunned to ‘discover’ these dark monuments of Miami’s history, know that you’re in the majority. Drs. Dunn and Price, and in subsequent phone calls with Dr. Enid Pinkney, the founder and keeper of The Historic Hampton House, and Ivy Bennett, program director of Arts for Learning (A4L), all repeatedly stressed that, by and large, Miamians, including Miami’s Black community, do not know this history. And as many of the individuals who do know it are in their 80s and 90s, their window to pass on this history is narrowing.

“Those Black residents who were here and living, those were the ones who informed us about the wall,” says Price of the South Miami wall. “We have since found out that the people who grew up in South Miami, Black people, always assumed that everybody knew about the segregation wall.” Her conversations with the community instead found that unless someone, White or Black, lived there while the wall actively served its purpose, its history was unknown.

“A lot of people don’t know there was a wall there, because the low thing they got there now that represents the wall doesn’t even look like a wall,” says Dr. Pinkney of the Liberty City wall, who recalls a “big controversy” when it came time to decide what to do with the divider once the neighborhood on both sides of the wall became occupied by Black residents. “You had some Blacks who didn’t want to remember anything about segregation, so they wanted it taken down. But then there were some of us — and I’m in that group — who wanted it to stay up there. In fact, we did not want the piece that was taken down to be taken down, because we wanted history. We wanted people to see how it was.”

“That was a symbol of how we were treated and disrespected back in the days of segregation,” Pinkney added. “I think that we need to have some evidence of that so this younger generation can understand.”

“What I’ve personally noticed is that more of the older or former residents, they knew the history,” said Bennett, leader of A4L’s Wall (In) program, a teen summer program and site-specific art initiative situated at the site of the Liberty City wall. “They were there when it was up, but the younger kids had no idea. Of all the students that we serve, I want to say maybe two of them have said, ‘Yeah, my Grandma told me about it’ or ‘I knew something, but not quite the full story.’ The majority absolutely did not recognize that this place where people kind of hang and congregate has this historical significance.”

The walls’ present and future

Students survey the wall as part of the Wall (In) program (Arts For Learning)

The Wall (In) program is the effort that’s furthest advanced the activation of any of these segregation walls as a means of preserving their history. The program, which had a few years’ run before taking a COVID-induced pause, is the brainchild of Tarell Alvin McCraney, a Liberty City native now famous as the co-writer of “Moonlight” who observed the lack of awareness about the wall while filming in the area. Though the wall was designated as historic in 2006, nothing exists on site to mark its significance.

“Our previous goal was that the students would have their monuments fabricated, and then those fabrications would be mounted there in perpetuity to make it an actual destination, much like Wynwood or any of the other artistic hubs here in Miami,” Bennett says of the project. “Now, as we’re thinking about it, we’re thinking about ways to duplicate this program in other historical neighborhoods that have these types of walls. So we want to do more iterations in Liberty City, but also in Coconut Grove, as well as other places where we’ve found there’s been these walls.”

Community activists and city administrators launch the South Miami Black History Mural (SOMI Magazine)

In South Miami, a group called United Survivors, of which Anna Price is a member, is pushing ahead on an effort to turn their community’s wall into a mural celebrating the neighborhood’s lost Black history. The group came together in the wake of George Floyd’s murder seeking to close the community’s divide.

“We were looking to revitalize or tell the history of black South Miami,” says Price. “We started to meet, and in that process, we started to talk with people, primarily women, who were pioneers in South Miami… in talking to these pioneers, they mentioned the wall.”

The effort was formally introduced last February. The mural, designed by local artist Gail Alexander with assistance from a researcher at FIU, will depict the once-vibrant heart of South Miami’s Black community, along with a portrait of Marshall Williamson, who was credited as being the first Black landowner in the area and known as the “Little Mayor” of South Miami’s African-American community. “This is to let people know what was here. We don’t want the history to get lost,” says Price, who, as a former administrator at South Miami Middle School and the University of Miami, wants area schoolchildren brought into the project’s fold.

When asked what she would like to see for the future of the walls, Dr. Pinkney, who fought to save the Hampton House from demolition and who continues to fight to preserve Miami’s Black history, had an urgent message, namely for Miami’s Black community: “Our problem is respecting our history. Not just respecting it, we’ve got to celebrate it. We’ve got to celebrate from whence we come. And as a part of that celebration should come some education,” she adds. “We need to be willing to make the sacrifice to do that, and if we do that, then other people will join us. We have to put in a whole lot of effort.”

“You know, I’ve gotten some things done,” said Pinkney, “but it wasn’t on flowery beds of ease.”